Blogging Fanghuiju:

State Surveillance, Propaganda Work, and Coerced Gratitude

Figure 1: As part of their training to do mass work among Xinjiang’s ethnic minority populations, a blogger’s work team watches a speech from Xi Jinping celebrating the 90th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army (《我为我们伟大祖国自豪,为强大的中国人民解放军骄傲》).

Click here to access the full collection of blogs, travelogues, and articles.

Since 2014, when Xinjiang’s authorities began carrying out the “Becoming Family” campaign (fanghuiju 访惠聚) and implementing the related “Four Togethers and Four Gifts” (si tong si song 四同四送) policies to guide mass work, a variety of blogs, travelogues, and news articles documenting this work have been published on the web (see the Glossary for more on fanghuiju and si tong si song). Some are success stories that emphasize the benevolence of the Party and its material impact on people’s lives, while others describe the work and its goals more broadly. Still, though they generally follow a formula, many of these sources are rich with detail not found elsewhere. One travelogue written by a primary school teacher from Beijing reveals that young children are sensitive to the word “detention” (收押) and associate police sirens with the possibility that their family members may be taken away. Others are noteworthy because they provide statistical information and the names of detainees, such as one post penned by a police officer that describes the physically demanding work of detaining hundreds of people per day. Many also include images of Uyghurs in shackles, flag-raising ceremonies, and ubiquitous police presence.

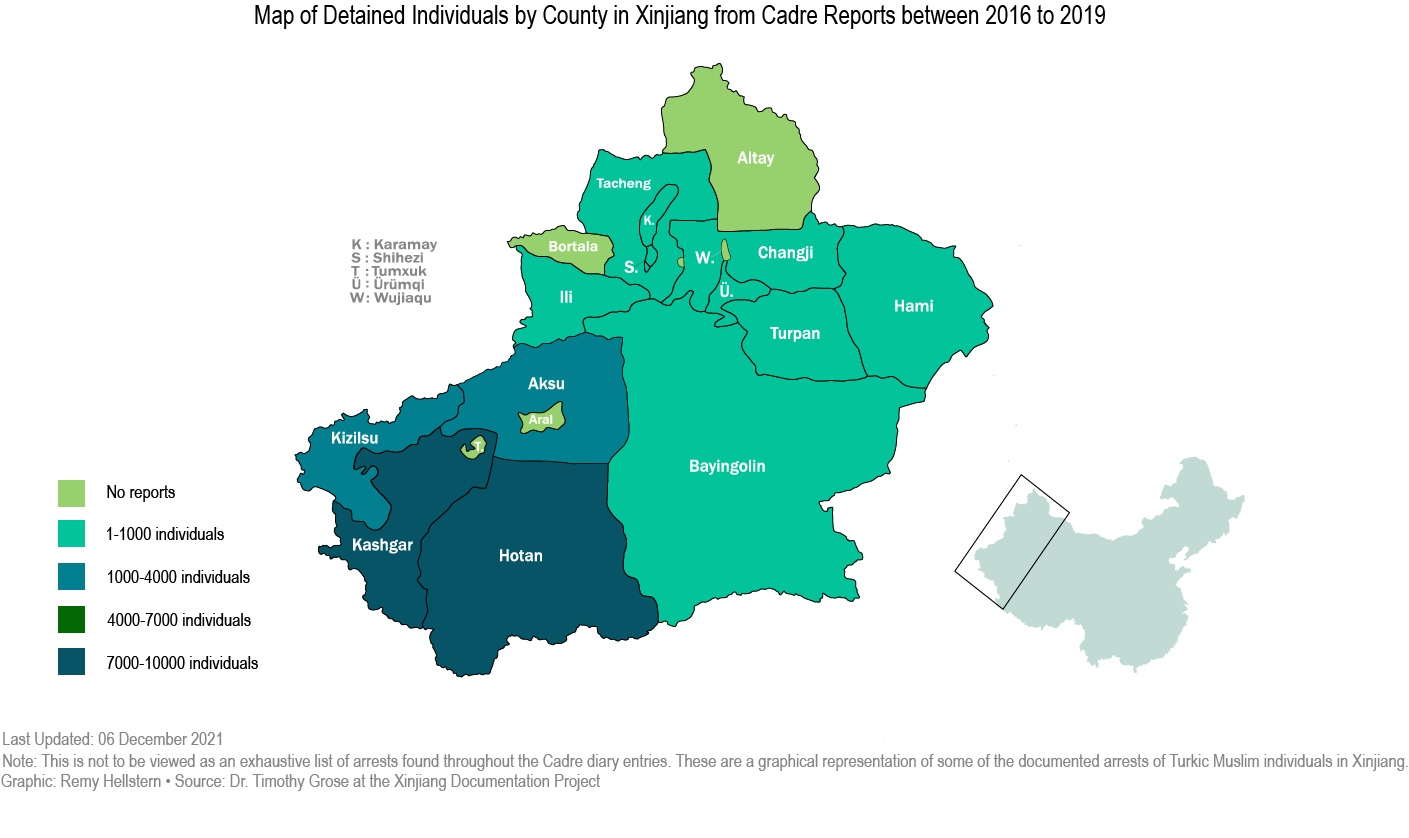

Figure 2: This map shows the regional breakdown by county of arrests found throughout the reports between 2016 and 2019.

Figure 2: This map shows the regional breakdown by county of arrests found throughout the reports between 2016 and 2019.

Yet, beyond attesting to the existence and scale of the extrajudicial detainment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in the region, these digital sources also present a unique window into how the agenda and strategies outlined in the fanghuiju cadre handbooks are being realized on the ground. They reveal the scope and mechanisms of surveillance embedded in this mass work, they document various methods of propaganda dissemination, and they speak to the CCP’s broader image-building project among Xinjiang’s ethnic minorities.

Figure 3: “During class, Teacher Zhang earnestly fills out the family visit form” (中班的张老师,在认真填写家访记录表). Collecting data on the families of detainees was a regular part of fanghuiju and si tong si song activities (《用心浇出美丽的花朵——记2017年10月支教家访工作》).

Surveillance

Although these sources do not account for the full array of the surveillance mechanisms deployed in Xinjiang, they nevertheless give some idea of its penetration into everyday life. Not surprisingly, much of the data collected pertains to Islam. For example, in addition to comparing how many adult males attended a flag-raising ceremony with mosque attendance earlier in the week, one source notes that a small work team took the identity of every single person attending a service and monitored the imam’s sermon to ensure that it adhered to state regulations. In another source, cadres asked families of the “three types of people” (三类人员 san lei renyuan) about a much broader range of issues: “family composition, animal husbandry, working away from home, economic conditions, and existing challenges” (家庭组成、畜牧业养殖、外出务工、经济结构现状、存在的困难). Notably, cadres are not the only figures responsible for collecting information about minority families. Another source describes how a group of Mandarin instructors visited their students’ families to inquire about issues such as “detentions,” “family populations and living situations” (家庭人口情况居住情况), and the presence of “outsiders” (外来人口). The involvement of these teachers reflects information found in the handbooks: these policies often reach families through their children.

Figure 4: A woman writes “ardently love the motherland” (热爱祖国) on a classroom chalkboard during a mass work meeting (《我为我们伟大祖国自豪,为强大的中国人民解放军骄傲》).

Fighting Extremism

Because blog entries written by cadres, teachers, police officers, and others carrying out fanghuiju activities in rural communities inevitably describe the day-to-day activities of the campaign, they contain a wealth of information about the nature of this propaganda work. Many describe large community gatherings, public events, and local talent shows. For instance, in celebration of the May Fourth Movement, Pishan County organized an event designed to promote modern culture and guide ethnic minority youths. It featured “stunning modern dancing, lively Sama dancing, highly instructive skits, rich and emotional poetry, modern and fashionable displays of clothing” (有劲爆的现代舞、欢快的萨玛舞、极具教育意义的小品、富有感情的诗歌朗诵、现代时尚的服装展示), and other activities.

These kinds of events, which are secular and explicitly couched in ideas of modernity, lie at the heart of the state’s deradicalization agenda. As an article describing fanghuiju activities in Mazarbeshi Village puts it: “modern culture shows the way and has built an atmosphere of anti-extremism” (现代文化为引领,营造了去“极端化”氛围). Authorities have also taken advantage of Islamic holidays—most of which are increasingly regulated or banned—to plan their own activities. In one Urumchi community, a fanghuiju work team spent Qurban, a major Islamic holiday, visiting the families of detained Muslims and promoting national unity. These efforts introduce secular elements to religious practices. In another example, one blog post featuring photographs of cadres visiting the families of detainees attempts to integrate the state’s deradicalization agenda with standard holiday expressions:

Qurban is almost here, let’s take a photo together!

Qurban is almost here, a little holiday gift sent with warm feelings.

Qurban is almost here, distribute propaganda to the relatives of people in vocational training.

Qurban is almost here, understand the illness and recuperation of the elderly.

(古尔邦节快到了,一起合个影吧!

古尔邦节快到了,一点节日礼物,送去了心意。

古尔邦节快到了,对教育转化人员亲属开展宣传教育。

古尔邦节快到了,详细了解老人的病情和康复情况。)

Figure 5: “The ‘I Am a Chinese Citizen’ Pledge” (“我是中国公民”宣誓词). Mass work in Xinjiang often involved activities that reinforced patriotism, including flag-raising ceremonies, photographs with the national flag, singing the national anthem, and taking oaths. (《感谢党 感谢政府的恩惠》).

Promoting Patriotism

National unity and patriotism are another constant in these blogs and articles. As these online sources show, love for the motherland is ritualized in a variety of group activities. In a blog post published by a Uyghur primary school teacher, she describes visiting her “relatives” in their homes to explain why their family members had been detained. After she and her husband, a police officer, finished with the legal propaganda work, they stood “beneath the national flag and sang the national anthem, swore an oath, and took a photo. These exercises not only increased our affection for each other, but also improved our thinking” (在国旗下进行了唱国歌、宣誓、合影等活动,这次活动不仅增近了亲戚之间的亲情,还在思想上有了提升). During a much larger gathering to celebrate the 68th anniversary of the founding of the PRC and the 19th National Congress of the CCP, more than 820 people belonging to ethnic minorities participated in a flag-raising ceremony. The flag, the blogger writes:

symbolizes the profound respect each ethnicity has for the great motherland, conveys our determination and confidence in defending national unity, defending social stability, and opposing national division, and further increases the patriotic feelings of ethnic minority cadres and the masses.

(她象征着我们各族人民对伟大祖国的崇高敬意,表达我们捍卫祖国统一、维护社会稳定、反对民族分裂的决心和信心,进一步激发各族干部群众的爱国情怀。)

Figure 6: A key component of mass work in Xinjiang involved offering condolences and household essentials as gifts to the families of detainees (《喜迎古尔邦节 送温暖慰问活动》.

Thanking the Party

Of all the messages put forth by officials and other fanghuiju workers, none is more consistent and pronounced than the idea that the CCP is benevolent and working hard for the benefit of the people. That the picture these sources paint is one of a giving Party and a grateful populace is not a surprise. Christian Sorace argues that the Party has repeatedly foregrounded this kind of narrative in order to preserve authority and stability in periods of crisis. In his book on the aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, he writes:

The new homes, roads, schools, and hospitals were proof of the Communist Party’s benevolence, power, and glory. In return for its generosity, the Party expected the recipients to feel as well as display a deep sense of gratitude. The ultimate acclamation of Party legitimacy would be for the earthquake survivors to acknowledge in words and deeds the contentment they were expected to find in their new lives (154).

Blog posts and articles praising mass work in Xinjiang conform to this story. As part of the fanghuiju campaign, and the si tong si song activities in particular, officials regularly brought families of detainees everyday items such as oil and grain. Many blog posts also indicate that they frequently helped families whose labour had been impacted by detentions. Alongside all of the gifts, condolences, and assistance with manual labour, the sources also document the degree to which the Party expects gratitude for its work in Xinjiang. In some instances, blog posts simply describe how cadres explain state policies in a way that highlights the compassion and generosity of the state. In others, expressions of gratitude for the Party’s work are intended for the blog post’s readers themselves. One source quotes an elderly villager:

The Communist Party is great, not only did they send me oxen and sheep, but they also pulled grass, swept the floor, and chatted with me about my daily life. I must teach myself and my family to stay away from extreme religious influences and illegal organizations, concentrate on wholeheartedly following the Party, and lead my family from poverty to become rich.

(共产党亚克西,不但给我送来了牛和羊,还给我拔草、扫地、和我拉家常,我一定要教育好自己的家人远离极端宗教和非法组织,一心一意跟党走,带领家人脱贫致富。)

Another post directly attributed to a man whose son had been detained echoes this sentiment:

Children are the future of the country and the hope of the family. The reason I’m telling my family’s story is, on the one hand, to warn and alert all heads of households that to be strict toward children is right and to spoil them is harmful. Properly teaching and leading children is the responsibility and obligation of every head of household. On the other hand, I want to genuinely thank the Party and government for educating and saving my son and saving my family! Please rest assured, the Party and the government, that henceforth I will definitely hold up the responsibilities of a father and teach and lead my child to walk a good path in life.

(孩子是国家的未来,也是家庭的希望。我之所以把我家的事说出来,一方面是要告诫、警醒各位家长,对孩子严是爱、宠是害,教育引导好孩子是每一位家长的责任和义务;另一方面就是要真心地感谢党和政府教育挽救了我的孩子,挽救了我的家庭!请党和政府放心,今后,我一定会负起一个父亲的责任,教育引导孩子走好人生路。)

These statements and the online sources in which they appear are designed to normalize extrajudicial detention, surveillance, and other policies targeting Xinjiang’s ethnic minorities. In this light, they also document the process by which the state has produced a new status quo by gradually escalating its penetration into everyday life. As Darren Byler writes, “As new levels of unfreedom are introduced, the project produces new standards of what counts as normal and banal.” Ultimately, these blog posts and articles provide a critical window into the state’s efforts to shape how ongoing developments are understood and how their history is told.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Associate Professor Timothy A. Grose for generously sharing this collection of sources.