The collection of media links below were either translated by the Xinjiang Documentation Project (Primary Accounts) or were originally shared by various media sources. The stories retell lived experiences of Uyghur, Kazakh, and other minority ethnic groups both before and during Chinese state repression. They are featured in a variety of mediums including articles, photo collections, and videos.

Primary Accounts

Anonymous, Xinjiang Documentation Project, 9 May 2019

In the Past Three Years, What Have I Seen in Kashgar’s Gaotai Neighbourhood?

This blog entry written by a Han woman, and translated by Chinese for Uyghurs, recounts her travels in Xinjiang and provides a rare glimpse into the everyday lives of Uyghurs living in a Kashgar neighborhood. The author recounts her friendship with Akbar and Muyesar, a middle-aged couple, and her descriptions feature candid conversations about their life histories, past hopes, and present anxieties. They met several times beginning in 2017, and upon returning to the neighborhood in 2018 the author learned that Akbar was given a 13-year prison sentence for issues with his cell phone. The Cadre Blogs section above features hundreds of similar social media and blog posts in the original Chinese.

Media Segments

Yasmeen Serhan, The Atlantic, 16 July 2022

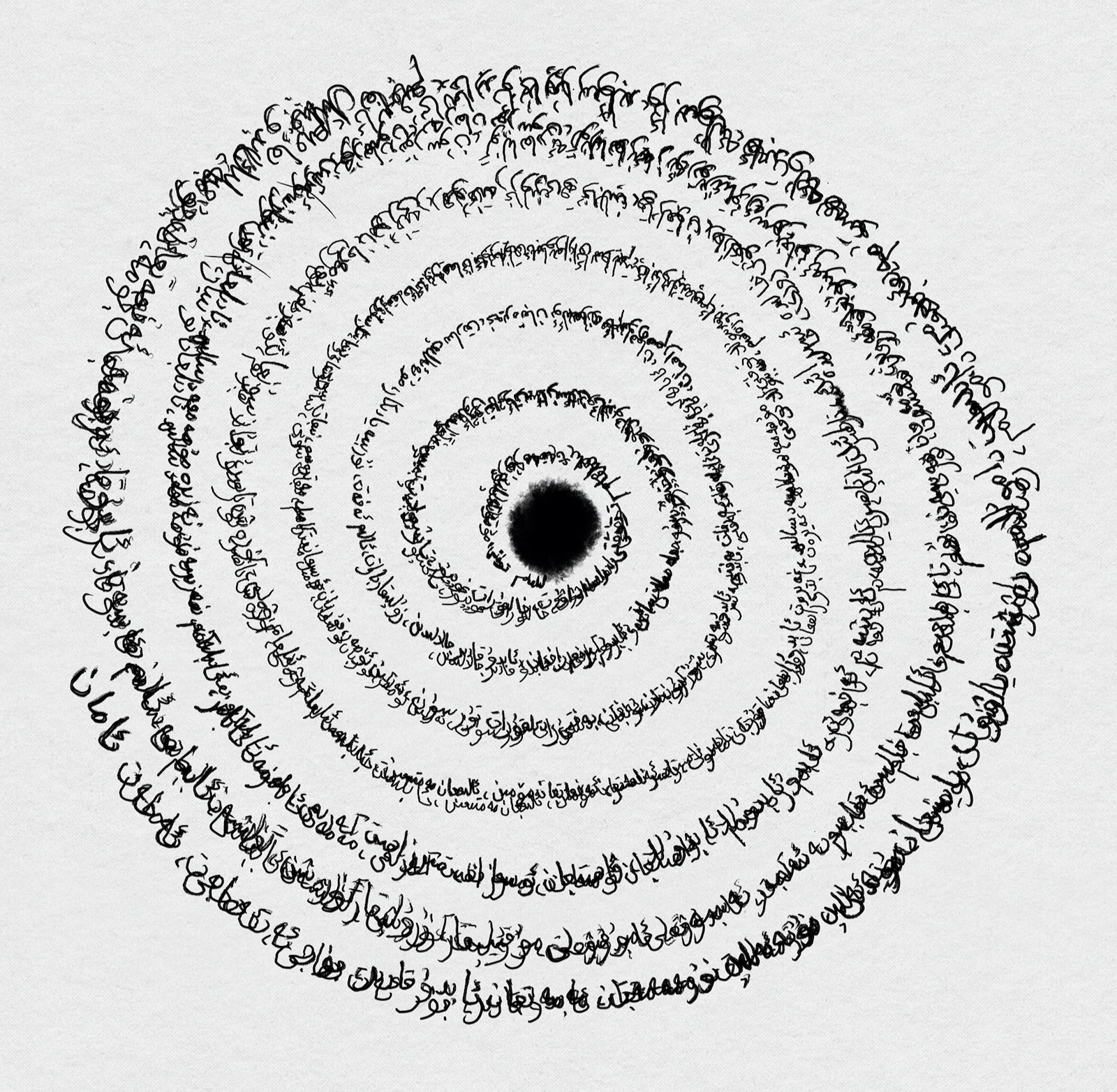

Uyghur Poems from a Chinese Prison

In this article, Yasmeen Serhan introduces and contextualizes recent poems by Gulnisa Imin, a poet and teacher of Uyghur literature who has been accused of promoting “separatism” and sentenced to over 17 years in prison. Despite writing in confinement, Imin and others have been able to smuggle their work out via prisoners who had memorized the verses before their release. Historian Joshua L. Freeman, who translated the the two poems published alongside the article, also discusses the central role poetry has played for Uyghurs during the current crisis.

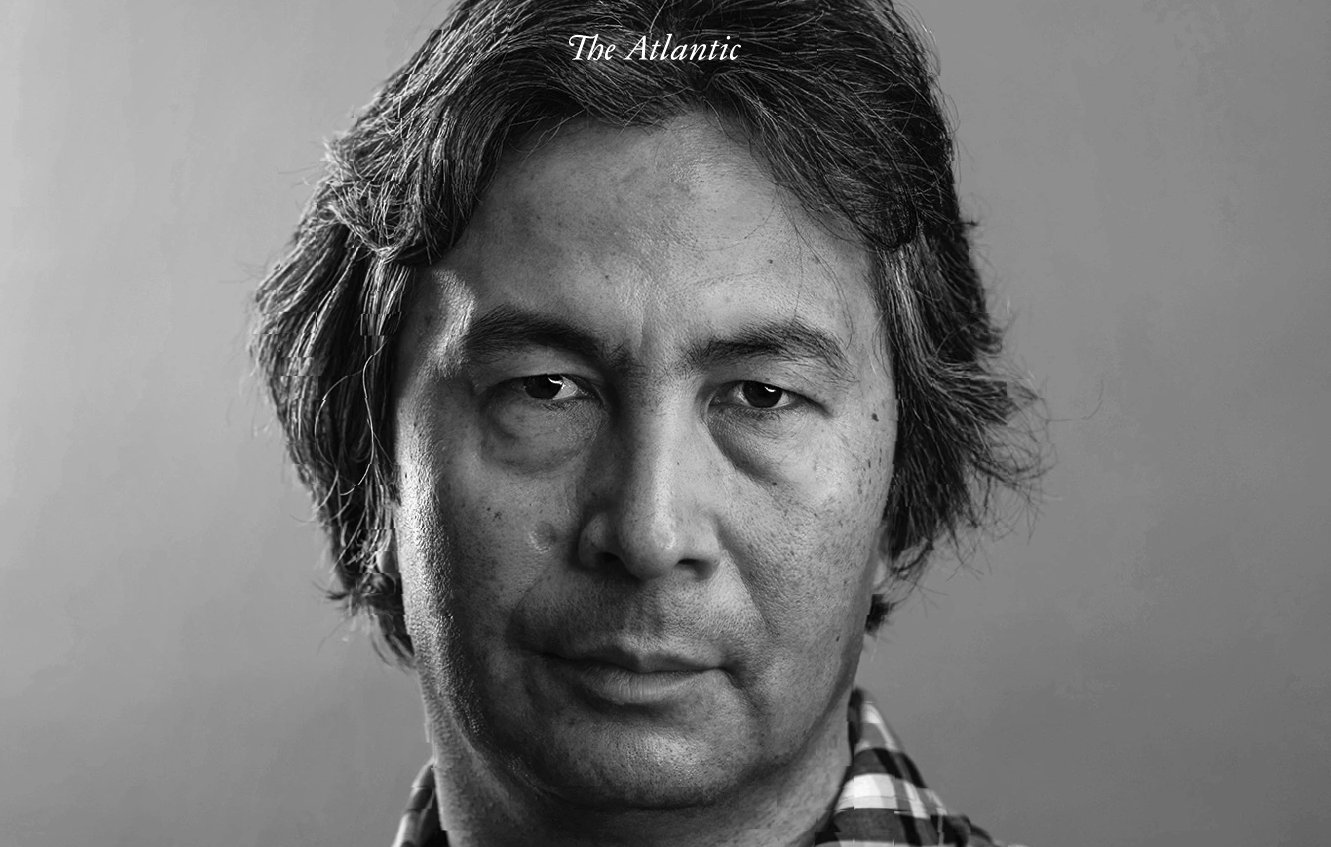

Tahir Hamut Izgil, The Atlantic, 14 July 2021

One by One, My Friends Were Sent to the Camps

In this five-part essay translated and introduced by historian Joshua L. Freeman, Tahir Hamut Izgil, a Uyghur poet from Xinjiang, recounts his family’s experiences in the region before they fled to the United States in 2017. Izgil writes about the arrests of close friends and acquaintances, the escalation of state surveillance, and the pervasive sense of fear that marked daily life in the wake of these developments.

Andrew McCormick, MIT Technology Review, 16 June 2021

Uyghurs outside China are traumatized. Now they’re starting to talk about it.

This article by Andrew McCormick on MIT Technology Review follows the personal struggles of Uyghurs who have left Xinjiang to reside elsewhere abroad. He captures their resilience and journey in coping with the toll the Chinese government’s crackdown had on them and their families; and the launch of therapeutic initiatives and treatments in the US that catering towards the Uyghur peoples and their traumas.

Brent E. Huffman, Vice World News, 21 May 2021

Pakistan Is Cracking Down on Uyghur Muslims Who Fled China

Brent E. Huffman’s piece on Vice World News follows how the Chinese government is leveraging its economic ties and assets with Pakistan, particularly through infrastructure loans, to deport Uyghur dissidents in Pakistan who have fled China for their safety and religious autonomy. The crackdown is being legitimized as a counterterrorism measure to subvert Uyghurs in Pakistan that allegedly are supporting the East Turkestan Islamic Movement that had committed terrorist violence in Xinjiang in 2005.

Damian Whitworth, The Times, 30 April 2021

My escape from a Chinese internment camp

Sayragul Sauytbay grew up in a semi-nomadic Kazakh family who lived along the border of Kazakhstan and China. She trained to be a teacher and has a loving family with a husband and two children. In July of 2016, they decided to move to Kazakhstan due to increasing securitization in the region. While her family made it across the border, as a public worker Sayragul was left behind while she tried to get access to her passport. Instead of reuniting with her family, Sayragul was sent to a re-education camp as a teacher. The following article highlights accounts of her new book, The Chief Witness, and explores what life is like in the “concrete coffin”.

Subi Mamat Yuksel, The Washington Post, 16 April 2021

Decades of service to China’s government didn’t save my Uyghur dad from prison

Subi’s father, Mamat Abdullah, followed all of the rules. An Uyghur man who was known for his dedication to community and intelligence. He was a well-respected member of the Chinese Communist Party, serving as the mayor of Korla in the 1990s and ultimately the chief of the regional forestry bureau. Despite this, in his mid-70s, Mamat was taken by the Chinese authorities ahead of a trip to the United States to visit Subi and her brother. Subi and her family’s life completely changed. In the article, Subi shares her experience searching for her father in the complex camp system and offers insight into the experience of Uyghurs living abroad.

Melissa Chan, The Atlantic, 08 April 2021

‘I Never Thought China Could Ever Be This Dark’ Leaving Xinjiang has not meant Uyghur women are free of Beijing’s grasp

The “crackdown needs to be understood as a multifaceted crisis”. Women often bear the brunt of maintaining and supporting families as their husbands, brothers, and fathers find themselves detained in China’s mass detention network. This Atlantic article follows the story of two Uyghur women who escaped from Xinjiang, only to find out their husbands had been detained separately from them. Leaving these women in an unfamiliar country with the responsibility of caring for their children while simultaneously having to be the sole providers for their families. Unsure of when they will see their partners again, these women have to navigate complex bureaucratic systems to acquire residency for themselves and their children all while dealing with the pain and loss they are experiencing.

Raffi Khatchadourian, The New Yorker, 05 April 2021

Surviving the Crackdown in Xinjiang

Offering one of the longest, most in-depth articles, Raffi Khatchadourian tells the story of Anar Sabit. Anar, a Kazakh woman from Xinjiang, strived to be a model citizen and student her entire life. After traveling abroad for work and school, Anar had to return home due to a family tragedy. She was not able to stay for long and upon trying to leave, she was swept into the mass detention system. This article provides historical context to the ongoing human rights crisis in the region and highlights one woman’s difficult journey trying to be released from the detention system.

Anar has written a series of poems as a way to heal from the fear and violence she experienced while detained. Readers can view those poems on Camp Album.

Ben Mauk, The New Yorker, 26 February 2021

Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State

Ben Mauk’s report traces the experiences of several detainees and their families to paint a picture of what life in Xinjiang has been like for the region’s ethnic minorities. The article is divided into chapters that describe, among other experiences, how Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities catch the state’s attention, endure detainment and reeducation, and witness the state penetrate into their daily lives through policies like the “Becoming Family” (fanghuiju) campaign. The report also features evocative infographics and audiovisual materials.

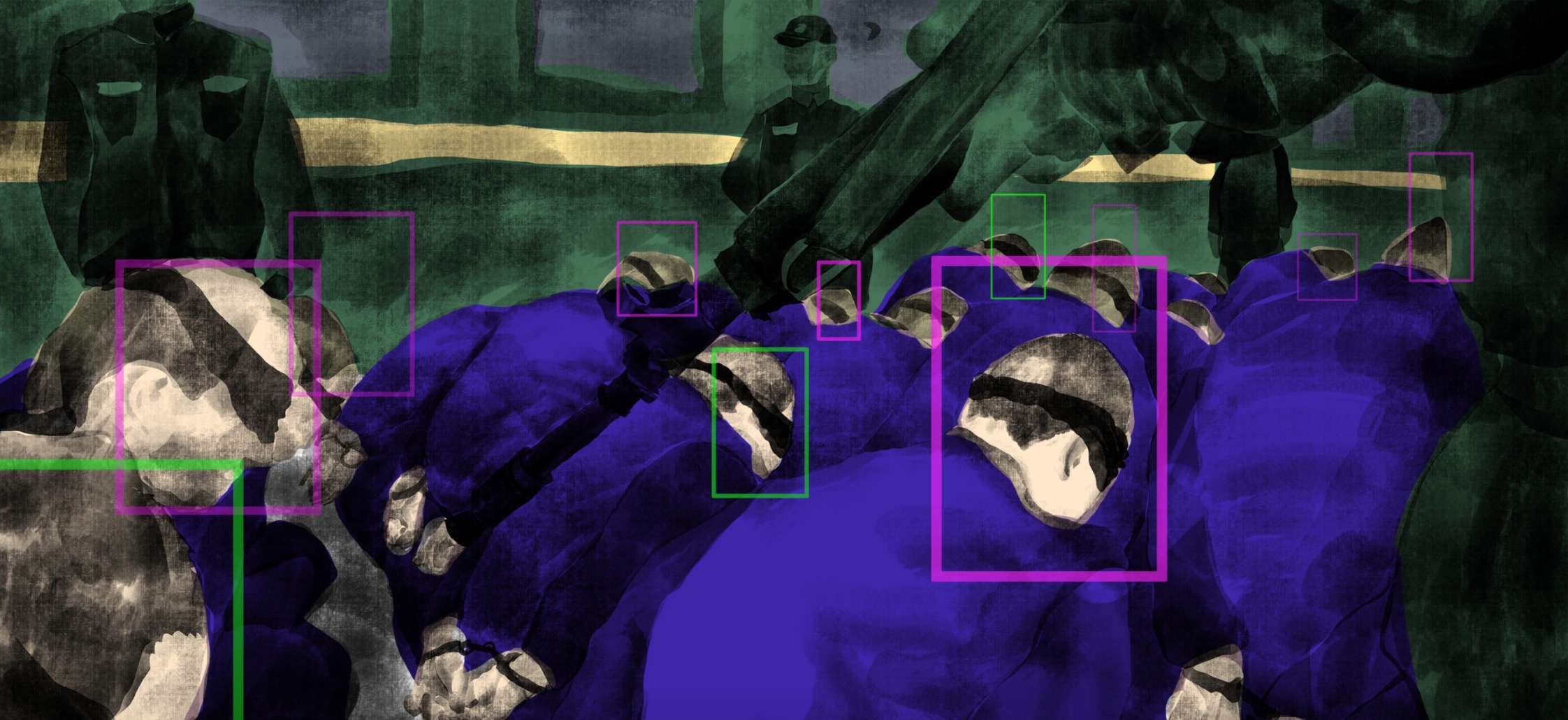

Matthew Hill, David Campanale, and Joel Gunter, BBC, 3 February 2021

‘Their goal is to destroy everyone’: Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape

“It is designed to destroy everyone’s spirit.” In this BBC report, Matthew Hill, David Campanale, and Joel Gunter interview former camp detainees and one teacher who reveal that organized acts of sexual assault and violence occurred frequently in Xinjiang’s “vocational education and training centres.” Some women recall being stripped and raped by groups of masked men in dark rooms, while others describe being tortured with electric shocks. These accounts offer critical testimony about conditions in facilities that the state has claimed are designed to support China’s ethnic minority populations.

Tahir Hamut Izgil, Newsline Magazine, 15 January 2021

How I Escaped China’s War on Uyghurs

“Having spent his entire life in Xinjiang, Tahir was unsure about moving his entire family to a new country. It wasn’t until he watched countless friends, neighbors, and acquaintances get detained and called in for questioning, that moving away seemed like the only option. One day, Tahir and his wife were called into the local police station and asked to fill out an invasive population collection form, ranking their trustworthiness among other demographic information. This article outlines what life is like for an average Uyghur family trying to weigh the cost of leaving their homeland and seeking asylum versus potentially risking detention and re-education.

Alice Su, LA Times, 17 December 2020

‘Will they let us live?’ Inside Xinjiang, survivors of China’s internment camps speak

“’You can’t speak with the people here. We’ve had too many negative reports from outside… Talking to locals would create a ‘security problem,'” said one official to a journalist during a confrontation in Korla. In this LA Times article, Alice Su provides an intimate account of life on the ground for Turkic Muslim groups living throughout Xinjiang in 2020. From Korla to Kashgar, Su reports near-empty Uyghur villages with an increased security presence, from QR codes on doors to prevalent facial recognition technologies to police checkpoints every few blocks. Su outlines the tactics being used to suppress the local population and the presence of targetted propaganda against Uyghurs. Despite the risks, Su uplifts Uyghur voices who recount their stories of extrajudicial detentions and loss of family members.

Timothy Grose, ChinaFile, 09 December 2020

How the CCP Took over the Most Sacred of Uighur Rituals

Weddings, funerals, baby-naming, and circumcisions are all important moments in Uyghur culture. These ceremonies reinforce the strong bond between family, neighbors, and friends as well as show a commitment to one’s religion. Dr. Grose knows this personally as he recounts a friend’s wedding he attended in 2010. Prior to 2015, Uyghurs were allowed to hold some private celebrations, much like the one Grose attended. However, after 2015 the presence of CCP members became mandatory at any cultural gathering or celebration. This invasion of privacy highlights the ways in which the CCP has involved itself in the everyday lives of Uyghurs, especially their most sacred rituals.

Darren Byler, Society and Space, 07 December 2020

The Digital Enclosure of Turkic Muslims

This piece highlights the creation of a digital enclosure, in the context of terror capitalism within Xinjiang, as a means to oppress Turkic Muslim groups. The article unpacks the interconnected relationship between technological innovation with the immense surveillance network in Xinjiang. The article looks chronologically at the policies that have been implemented within the region and how they have been leveraged to create a “forced labor regime”.

Joshua Freeman, The New York Times Opinion, 23 November 2020

China Disappeared My Professor. It Can’t Silence His Poetry.

In early 2018, Joshua Freeman learned that his professor and friend, Abduqadir Jalalidin, had been sent to a re-education camp in Xinjiang. Renowned poet and teacher Jalalidin did not let his incarceration silence him. As Freeman writes, “my professor’s poem is also testimony to Uighurs’ unique use of poetry as a means of communal survival”. Jalalidin’s words speak truth to power as he highlights the true conditions within re-education centers and reminds us of the resiliency of people.

Darren Byler, SupChina, 04 November 2020

‘The atmosphere has become abnormal’: Han Chinese views from Xinjiang

In this piece from Dr. Byler, he explores what it means to be a ‘Xinjiang Han’ in a police state. The article follows the stories of Meng You and Kong Yuanfeng as they negotiate the complicated relationship between Hans and Uyghurs throughout the region. Despite having positive interactions with Uyghur people and the feeling of unease about the policies in place, these testimonies highlight the continued importance of ethnic solidarity (民族团结 Mínzú tuánjié) to Han Chinese.

John Phipps, 1843 Magazine, 15 October 2020

“If I speak out, they will torture my family”: voices of Uyghurs in exile

This long-form article follows the stories of Uyghurs in London as they try to negotiate life in exile. The stories touch on the constant feelings of unsafety, the lack of ability to discuss the traumatic events that happen to them, and whether or not you can truly escape the watchful eye of the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, the main surveillance system in Xinjiang.

Darren Byler, NOEMA Magazine, 8 October 2020

The Xinjiang Data Police

Baimurat didn’t know what he signed up for when he was recruited to work as assistant police by the local Public Secretary Bureau. Unknowingly, he had agreed to start policing his local, Uighur and Kazakh, community members from behind a screen monitoring faces and movements. The following story explores the rise of big data policing in China and how technology has been leveraged as a tool to surveil minority populations in Xinjiang. Baimurat is an example of the many low-wage young workers that maintain and program the “counterterrorism swords” wielded by the government to monitor the people of Xinjiang.

Joshua Lipes, Radio Free Asia, 18 September 2020

Uyghur Youth Held After Posting Rare Videos Criticizing Government From Inside China

Between Sept 2 and Sept 4, Miradil Hesen, a young Uyghur man, posted a six-part video series on Youtube criticizing the punishment he received from the Chinese Government for accessing foreign internet, specifically Instagram. Hesen discusses the implication of these charges have his family members, like his grandfather’s inability to access his pension due to the charges and acts of sexual violence against his mother. Hesen dedicates multiple videos to discussing gender violence in Xinjiang, referencing his mother who he claimed was forcibly sterilized by the CCP and had to seek treatment for uterine cancer as a consequence of the procedure. Currently, his whereabouts are unknown.

Al Jazeera Media Network, September 2020

Living in the Unknown

Living through the Unknown is an interactive long-form article and a VR documentary that emphasizes the struggle of Uighur populations living away from China. There is an interactive component where the reader can follow the lives of four young women fighting to preserve their culture and heritage. The VR documentary tells the story of three different people as they struggle with losing contact with their family members in China, producing a feeling of hopelessness akin to being in limbo.

Ruth Ingram, The Diplomat, 17 August 2020

Confessions of a Xinjiang Camp Teacher

In 2017, Qelbinur Sedik was summoned to a town hall and told that she was one of the brightest teachers in her school. The local government told her she would be helping to teach Chinese to groups of ‘illiterates’ and needed to sign a confidentiality agreement before she began. Sedik had unknowingly agreed to work at one of the vocational training centres in Xinjiang. The following article is an account of what it was like to work in these facilities and documents the horrors experienced there. Sedik’s tale tells of forced sterilizations, removal of limbs, unhygienic conditions that lead to lasting, sometimes fatal, health complications, and what it’s like to lose your students in front of your eyes. Currently, Sedik has fled to Europe where she has recounted her story to the Dutch Uyghur Human Rights Foundation.

Joshua Freeman, The New York Book Review, 13 August 2020

Uighur Poets on Repression and Exile

Joshua Freeman’s article traces the lives of several Uighur poets who are currently in exile. The way the diaspora deals with the crisis in the homeland, the sense of loss and the unique nature of poetry give a voice to unspeakable experiences of violence and oppression and provide an account of grief and survival.

James A. Millward, Medium, 4 August 2020

Wear your Mask Under your Hood: An Eyewitness Account of Arbitrary Detention in Xinjiang during the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic.

This account follows the story of Merdan Ghappar, a young Uyghur artist and former dancer, who was held in captivity in a police station in Kucha, Xinjiang. After being moved to a new facility in Guangzhou due to fears surrounding the coronavirus outbreak, he was able to retrieve his phone and contact relatives in Europe. His family received text messages from Ghappar outlining the meager conditions of holding facilities and accounts of psychological and physical abuse. They have not heard from him since.

Darren Byler, SupChina, 1 July 2020

The Imprisonment of the ‘Model Villagers’: Two Uyghur Sisters on What It Means to Lose Their Family and Way of Life.

A “5-Star Model Civilized Family” who once had a “small red plaque with five stars on it to the front gate of their house” became targeted by the authorities for the “crime” of studying in Turkey.

Cha Naiyu, Amnesty International, 16 June 2020

Witness to Discrimination: Confessions of a Han Chinese from Xinjiang

This testimony was written by a Han Chinese person growing up in Xinjiang documents the systemic repression and discrimination that his Uighur peers suffered over the years.

Ira Glass, This American Life, 17 April 2020

Black Box

This episode of This American Life focuses on the story of Abdurahman Tohti and his family who are separated between Xinjiang and Turkey. It shows how China’s grip on Uighur bodies extend beyond the border and showcases the average everyday life of one family under state surveillance, fear of prosecution, and yearnings for family intimacy.

Gene A. Bunin, Foreign Policy February 2020

Xinjiang’s Hui Muslims Were Swept Into Camps Alongside Uighurs

Gene A. Bunin’s piece on Foreign Policy tracks the emerging trend of repressions against Hui peoples in China. While most of the crackdowns against Muslims in China have been against Uyghurs, the Huis, who are also of Muslim faith, have traditionally been closer to the country’s majority ethnic Han, in language, culture, and appearance; and such ties have been attributed to the very low number of crackdowns against Hui citizens. However, new revelations of arrests of Hui peoples suggest the opposite.

Amnesty International, February 2020

Nowhere Feels Safe

This piece from Amnesty International documents the experiences of Uyghurs living abroad, who also feel reluctant to talk about their relatives living in Xinjiang, over fears of further retaliation.

Sarah A. Topol, The New York Times Magazine, 29 January 2020

Her Uighur Parents Were Model Chinese Citizens. It Didn’t Matter. Witness to Discrimination: Confessions of a Han Chinese from Xinjiang

This chronicle traces the lives of a “model” Uighur family’s experience of everyday racism, increasing state violence, and eventual internment in “reeducation” facilities despite toeing the party line at every turn.

Gene A. Bunin, The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, 13 December 2019

“There Was No Learning at All”

Abridged first-person account of Xinjiang camp eyewitness Nurlan Kokteubai, delivered at the office of the Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights organization on November 5, 2019.

Nmslese, China Digital Times, 4 November 2019

“What’s Happening in Xinjiang: An Account in Southern Xinjiang during a Visit with Several Party Cadres.”

Nmselese writes about their eye witness account as an ex-CCP journalist during a visit to southern Xinjiang in 2018. They document the differential treatments from the authorities towards Han Chinese and Uyghurs. For instance, at checkpoints, Han Chinese can get through easily while Uyghurs have to be searched thoroughly and many other banal, but revealing details.

Gene A. Bunin, The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, 1 November 2019

“Because you had to do it very quickly, or you could be punished.”

A summary of the interview with Xinjiang camp eyewitness Tursunay Ziyawudun, done at the office of the Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights.

David Stavrou, Haaretz, 17 October 2019

A Million People Are Jailed at China’s Gulags. I Managed to Escape. Here’s What Really Goes on Inside

Rape, torture and human experiments. Sayragul Sauytbay offers firsthand testimony from a Xinjiang ‘reeducation’ camp.

Joshua Lipes, Believer Magazine, 1 October 2019

Weather Reports: Voices from Xinjiang

This piece from The Believer features Berlin-based journalist Ben Mauk, who interviews Xinjiang survivors who are now living in Kazakhstan.

Matt Rivers and Lily Lee, CNN, 9 May 2019

Former Xinjiang teacher claims brainwashing and abuse inside mass detention centers

A former employee at a Xinjiang re-education camp recounts of horrific stories of abuse and indoctrination.

AFP, Hong Kong Free Press, 22 March 2019

Eat pork, speak Chinese, no beards: Muslim former detainee tells of China camp trauma

For Muslims in China’s re-education camps, indoctrination starts with early morning patriotic songs and sessions of self-criticism, and often ends with a meal of only pork, according to one exiled former detainee.

Katrin Kuntz, Spiegel International, 13 November 2018

An Inside Look at China’s Reeducation Camps

Ex-prisoners who have escaped across the border to Kazakhstan talk about their imprisonment.

Foreign Policy, 28 February 2018

A Summer Vacation in China’s Muslim Gulag

This article from Foreign Policy features an account of Iman, a university student of Uyghur descent studying in the United States, who found himself incarcerated for no reason in a Xinjiang detention centre when returning home for summer break. He was later released and allowed to return to the US, before being warned to be careful of what he says in North America.