“Hundred Questions and Hundred Examples”:

Cadre Handbooks in the Fanghuiju Campaign

Figure 1: “The Kezhou Party Leadership Inspects and Guides Village Work.” The handbooks train cadres how to embed themselves in communities, earn the trust of villagers, and carry out the fanghuiju campaign’s goals of promoting patriotism and rooting out ‘extremism.’ (“Hundred Examples” [百例] Volume 1 [上册], 4).

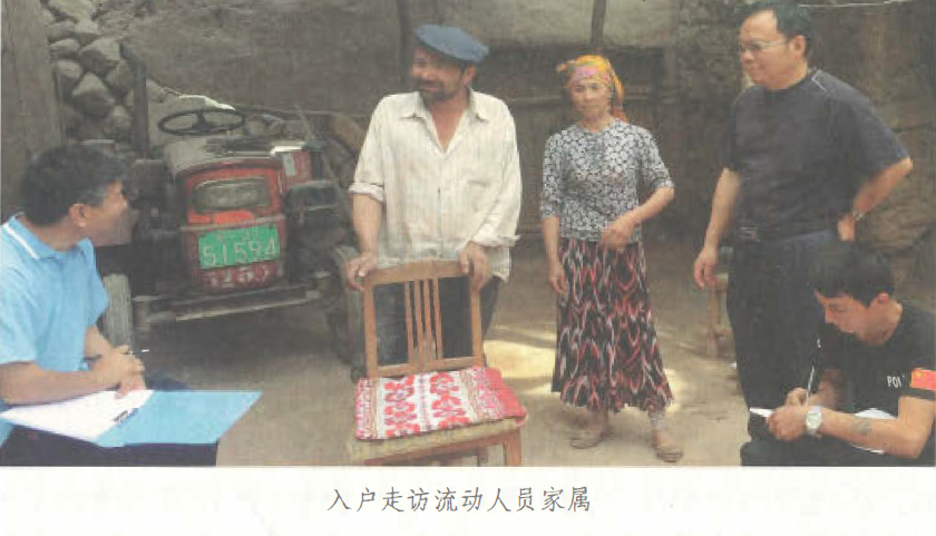

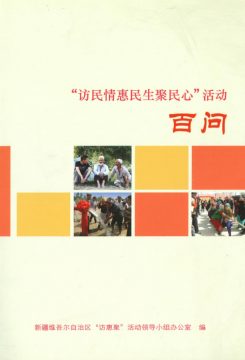

These three handbooks are designed to educate grassroots cadres as they implement the “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Bring Together the Hearts of the People” [访民情、惠民生、聚民心] campaign (see the Glossary of this site)—hereafter referred to as fanghuiju [访惠聚]. The campaign, which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began to carry out in 2014, calls for cadres and work teams to go door-to-door in their communities and interview Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other ethnic minorities (see Figures 1 and 2). The handbooks’ introduction describes the campaign’s goals as social stability and long-term peace. Among other approaches and strategies, the handbooks call for an “insistence on compliance to the rule of law in Xinjiang, unity and stability in Xinjiang, and the long-term construction of Xinjiang,” (坚持依法治疆、团结稳疆、长期建疆) as well as for “the reinforcement of grassroots Party-building, the promotion of religious harmony, and the production of theoretical exploration, fresh practice, and innovations in mass work” (加强基层党建、促进宗教和谐、做好群众工作的理论探索、鲜活实践和创新成果).

Figure 2: “Visiting the Household of a ‘Migrant Family.’” A Party official interviews a family as part of the fanghuiju campaign. (“Hundred Examples” [百例] Volume 2 [下册], 48).

The red book, referred to as the “Hundred Questions” [百问], covers the overall mission of fanghuiju, offers interpretations of policies, analyzes theory, and instructs on how to deal with complex situations that may arise. It is divided into 200 chapters, each phrased as a question and attributed to a particular work team or Party institution. For example, the office of the lead group carrying out Kezhou’s fanghuiju campaign was responsible for a chapter titled “How to Make ‘Grassroots Preachers’ a Force for Educating and Disseminating Propaganda to the Masses?” (如何让‘草根宣讲员’成为宣传教育群众的有生力量?). The orange and green books are volumes one and two of the “Hundred Examples” [百例], a complementary collection of 200 chapters also attributed to a diverse group of organizations. The “Hundred Examples” showcases “innovative practices and successful cases” (创新做法、成功案例) for other cadres to emulate as they carry out the fanghuiju campaign. Taken together, the contents of the three books are positioned as “the crystallization of the practical experiences and collective wisdom” (实践经验与集体智慧的结晶) generated by the campaign.

Figure 3: “Villagers Take the Initiative to Turn Over the ‘Three Forbidden’ Items.” These items include objects for certain Islamic practices, media ‘illegally’ distributed over the internet, and books, posters, and other texts ‘illegally’ published in print. (“Hundred Examples” [百例] Volume 2 [下册], 53).

Broadly, the campaign is designed to monitor Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other ethnic minorities in order to promote identification with China and weed out ‘radical’ Islamic beliefs and practices (see Figures 3 and 4). Some chapters offer clarification of policies and logistical advice for this work, including advice for carrying out household visits, dealing with “difficult-to access-households” (门难进), and detaining members of a family. Many others emphasize how cadres can target social and cultural activities like education, recreation, and family life to accomplish fanghuiju campaign goals. The agenda underlying this emphasis on daily life accords with David Brophy’s assessment—in his article “Good and Bad Muslims in Xinjiang”—of the state’s overall approach to fighting “the three forces”: extremism, separatism, and terrorism (see the Glossary of this site):

“the premise of [the state’s] liberal view is that when ‘extremist’ ideology penetrates the Muslim community, it puts some, but not all of its members on a path towards radicalisation… From this premise an elaborate discourse has arisen, purporting to scientificity, which allows security agencies to identify ‘at-risk’ individuals and take steps to rehabilitate them.”

In this light, the cadre handbooks identify critical points in everyday life at which cadres carrying out fanghuiju can intervene. Chapters instruct how cadres can influence families through their children, take advantage of summer vacations to promote Chinese-language learning, encourage women to promote “civilized qualities” (文明素质) (see the Peasant Paintings series), and use night markets to disseminate propaganda.

Figure 4: “Launching the “Take a Photo with The National Flag” Campaign.” One of the primary goals of the fanghuiju campaign is to persuade Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other ethnic minorities into valuing a Chinese identity over a Muslim identity. (“Hundred Examples” [百例] Volume 2 [下册], 92).

A significant number of chapters also concern labour, financial issues, and access to jobs. Since the economic reforms instituted by the CCP in the 1980s and 1990s, Xinjiang’s industries have been bolstered by an influx of Han workers from Eastern China. Darren Byler, in an interview with New Internationalist, “Living in a Ghost World,” presents the Uyghur grievances for not benefiting from the region’s growing economy:

“[Uyghurs] saw the cost of living begin to rise, but they also felt themselves excluded from the new economy because most of the jobs—especially in the lucrative oil and natural-gas sector—were not offered to them. They saw themselves becoming poorer in relation to the people around them and more desperate in terms of how they would provide for their families and create a better life for their children. Those are the conditions that have produced a lot of the tensions and violence in the region.”

The result of this economic transformation has been increased poverty within villages and an increasing number of young men leaving their homes to find work in urban areas. The cadre handbooks reflect the CCP’s concerns about how this immiseration has opened up space for extremist thinking, and they reveal how the fanghuiju campaign seeks to remedy the problem. Chapters dealing with Uyghurs who have migrated to cities in search of work emphasize harmony, and they call for the integration and surveillance of this “floating population” (流动人口) in their new communities. At the same time, chapters dealing with how Xinjiang’s economic transformation has impacted villages tend to emphasize the alleviation of poverty. They contain instructions for cadres on how to help work groups organize relief for the poor, how to set up “courtyard economies” (庭院经济) for dried apricots and other goods, and how to get villagers into the workforce.

The cadre handbooks offer a rare glimpse into CCP thought work on the ground—they reveal work methods, mechanisms and strategies, prevailing challenges, and overall goals. Given that these volumes were produced collaboratively by work teams and organizations at a variety of levels and locations, and that they contain photographs documenting many aspects of the campaign, they are also a valuable window into the state’s ongoing efforts to “deradicalize” Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other ethnic minorities throughout Xinjiang.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Associate Professor Timothy A. Grose for generously sharing these sources, and to the staff at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology’s Logan Library for making them available digitally.

For English translations of the Cadre Handbook, find link here.

|

百问 (Hundred Questions) |

|

百例 上册 (Hundred Examples Volume One) |

|

百例 下册 (Hundred Examples Volume Two) |